|

Part 3 |

|

Part 3 |

|

This is one of a series of pages of

Medieval and Renaissance illustrations of trebuchets. To avoid problems

with historical interpretation (& copyright!) as much as possible,

I have chosen to use pictures which seem to be plausibly contemporary

with the devices being illustrated. I have also tried to avoid what

seem to be obvious fantasy pieces. . |

| No. 9 - Siege of Jerusalem |

It shows two trebuchets in use next to a wheeled siege tower. The trebs

are fairly basically drawn, but show the main features - a box of

rocks, a sling containing the projectile, bracing timbers on the

uprights and a timber base.

It shows two trebuchets in use next to a wheeled siege tower. The trebs

are fairly basically drawn, but show the main features - a box of

rocks, a sling containing the projectile, bracing timbers on the

uprights and a timber base.

There is, of course, an alternative use for wheels on trebuchets.

Many illustrations on these pages imply that trebuchets in their

operating positions were subject to enemy arrow fire and siege engine

counter-battery. If an assembled machine could be hauled into position

(perhaps with its bucket unloaded) it would not have to be built under

fire. Wheels would be one way of doing this - although giving the

machine a sledge-like base and dragging it also seems plausible. Once

in place the trebuchet need not have been left free-moving .. it might

also have been anchored or chocked.

As a final word, it seems hard to imagine how or where you would fit wheels to something like Villard de Honnecourt's base. Those side-bracing transverse timbers present quite a challenge.

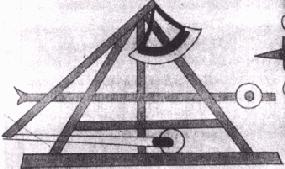

| No. 10 - "Mongol" Trebuchet |

Compare this machine to the trebuchet shown in illustration No.8...

Compare this machine to the trebuchet shown in illustration No.8...There is a winch at the rear of the machine, and the engineer is wielding a mallet, presumably to trigger the trebuchet.

Note that here too the artillery is within bowshot of the defenders.

| No. 11 - "Saray album" |

Here it can be seen in the rest position, the throwing arm of its beam pointing straight up, indicating that the other beam end is much heavier. Although the base supports obscure the other end of the beam, it is very likely that this is a either a purely or partly weight-powered (rather than purely "traction") trebuchet. As no pulling ropes are to be seen connected to this short arm, we can hazrd that this is, in fact, completely weight powered.

The drawing is unusual in showing a weight/arm assembly that fans out

very widely - it's visible on both sides of the frame's timbers - and

which appears to be rigidly attached to the beam.

Though some modern reconstructions (especially the big ones) use this

system of a solid weighted beam, not many historic pictures do.

Some French historians prefer to call trebuchets with rigidly-attached weights "mangonels". This might be one, Illustration No.7 another..

Other features to note in this image are:

| No. 12 - Hasan al-Rammah |

This simple drawing of a Middle Eastern machine shows the same shape of counterweight as the machine shown in Illustration No.11.

This simple drawing of a Middle Eastern machine shows the same shape of counterweight as the machine shown in Illustration No.11.

Note that this machine's counterweight is not rigidly attached to the end of the beam, but is instead hanging from it like most of the other trebuchets on this page.

It is interesting to ponder why the builder has gone to the trouble of

giving the weight a curved shape. The curve of the base is roughly a

circle centred on the suspension point of the weight on the beam.

Certainly this would allow the base's frame to be made lower, since no

clearance would need to be given for the corners of the weight, but

this seems hardly likely (or worth the effort). Any ideas?

| - NAVIGATION -

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

|

Previous | Next |  |

|

| Page |

|

Page | ||