In Re Dürer

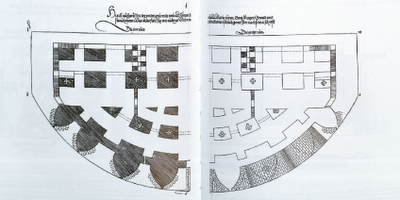

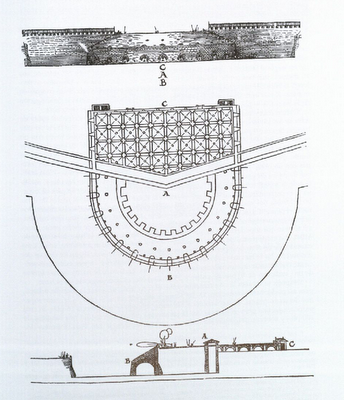

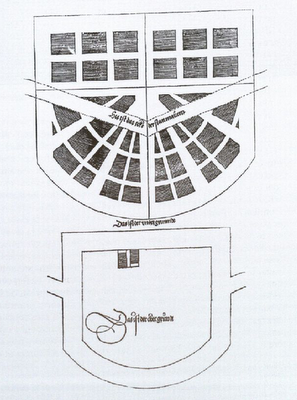

Montage of Ramparts and Plan of Dürer's fest schloß (fortified citadel), after his Etliche Underricht zu Befestigung der Stett, Schloß und Flecken

(1527) [Source: Juan Luis González García, “Alberto Durero, Tratadista

de Arquitectura y Urbanismo Militar”, in Alberto Durero, Tratado de Arquitectura y Urbanismo Militar (Madrid: Ediciones Akal, 2004), p. 39].

Montage of Ramparts and Plan of Dürer's fest schloß (fortified citadel), after his Etliche Underricht zu Befestigung der Stett, Schloß und Flecken

(1527) [Source: Juan Luis González García, “Alberto Durero, Tratadista

de Arquitectura y Urbanismo Militar”, in Alberto Durero, Tratado de Arquitectura y Urbanismo Militar (Madrid: Ediciones Akal, 2004), p. 39].In 1527, Albrecht Dürer published his treatise on military architecture, the Etliche Underricht zu Befestigung der Stett, Schloß und Flecken ("Various Instructions in the Fortification of Cities, Castles, and Towns"). Though Dürer’s works are numerous, and though the artist’s work inspired an expanding field of interpretative work for centuries, the Etliche Underricht nevertheless remains a curious cipher, a footnote in Dürer’s work and legacy. Thus William Martin Conway, in his Literary Remains of Albrecht Dürer from 1889, claims that the Etliche Underricht “presents few matters of interest” to the student of art. Erwin Panofsky’s influential The Life and Art of Albrecht Dürer (1943) makes no mention of the Etliche Underricht. The artist fares much worse when analyzed by military historians and historians of science. Simon Pepper, in his study of military architects and aristocrats, tells us that “despite its excellent illustrations and specialist content,” Dürer’s treatise “did not evidently exercise great influence outside the German-speaking world.” Christopher Duffy, in his study of siege warfare, tells us that Dürer’s treatise “remains an isolated, North European attempt to meet the challenge of problems that were already finding more convincing solutions in Italy.” Historian of science Jãnis Langins declares that the Etliche Underricht “was more of an architectural fantasy than a practical manual for fortifiers.” The list of less-than-favorable references continues.

When considering its architectural merit, however, we can detect some initial, yet productive confusion as to the actual innovations of Dürer’s “architectural fantasy.” Hanno-Walter Kruft, for example, declares that the Etliche Underricht is the first printed treatise dealing exclusively with fortifications. Yet Dürer’s manual was not the first treatise on military architecture. A distinction must be made between print and manuscript. Thus in 1482, Francesco di Giorgio Martini circulated his own illustrated treatise on military architecture, the Trattato di Architettura, Ingegneria e Arte Militare, but only in manuscript form. The Etliche Underricht’s status as the first printed treatise devoted solely to architecture using original images also deserves some interrogation. This category is constructed carefully: though Fra Giocondo published his illustrated version of Vitruvius’ Ten Books in 1511, it useful to bear in mind how that treatise did not originally feature images. Nor was it a treatise that dealt exclusively with architecture. Alberti’s De Re Aedificatoria, though published in 1482, did not appear with illustrations until Cosimo Bartoli’s 1550 translation. The Etliche Underricht preceded the next great architecture treatise, Serlio’s Regole Generali d'Architettura by 10 years.

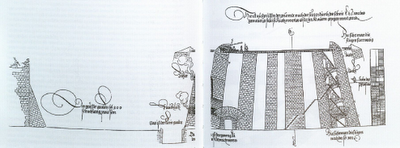

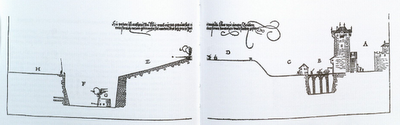

Albrecht Dürer, Geschützrondellen (“Rounded Fortification”), plan, section, elevation, woodcuts from Etliche Underricht zu Befestigung der Stett, Schloß und Flecken (1527)

Albrecht Dürer, Geschützrondellen (“Rounded Fortification”), plan, section, elevation, woodcuts from Etliche Underricht zu Befestigung der Stett, Schloß und Flecken (1527)But when it comes to issues of architectural convention, we are on firmer ground. Mario Carpo observes how the Etliche Underricht was the first treatise to show a complete set of plans, sections, and elevations for an individual project, anticipating Bramante’s designs for the cupola at St. Peter’s by 13 years. Yet Renaissance art and architecture historian John Pinto’s study of the origins of ichnographic city plans points out parallel developments between Leonardo da Vinci’s plans for the city of Imola from 1503 and Raphael’s distinguishing between plan, section, and elevation in his letters to Leo X from 1513-1521 , stating that both of these are the foundations for a “new form of architectural drawing.” Considering that Dürer also resorts to the architectural convention of depicting projects in plan, section, and elevation, and further considering that it is unclear whether the author of the Etliche Underricht knew about da Vinci’s or Raphael’s own thoughts on orthographics , we could very well tow the line taken by our esteemed military historians – namely, that Dürer’s treatise is an isolated instance, a mere footnote in the history of architecture.

Here, however, I would like to identify possible trajectories for locating Dürer’s Etliche Underricht within a history of architecture treatises. An investigation into the architectural significance of this treatise necessarily begins with a brief foray into Dürer’s own background in architecture, the Entliche Underricht itself, as well as his exposure to existing texts on architecture. With this context firmly in place, it is then possible to continue exploring ways of articulating an architectural significance for the Entliche Underricht.

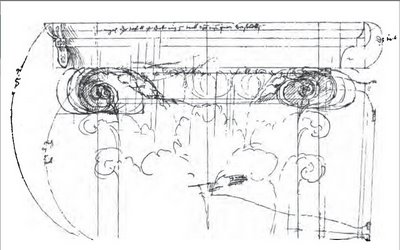

Two basic types of works constitute Dürer’s early architectural output: sketches and drawings of classical subjects, as well as annotated drawings of various design commissions in Nuremberg. Although Conway tells us that Dürer thought of architecture as an art subject to individual capriciousness, he does see value in the myriad architectural notes interspersed throughout a draft of Dürer's Four Books on Measurement – a testament to the influence of Vitruvius. One of Dürer’s notes accompanying the Four Books, for example, features a large sketch of a Corinthian capital. This sketch contains a series of regulating lines -- evidence of Dürer actively working out the proportional calculus from Vitruvius’ work. This is, however, an ultimately unsuccessful endeavor, according to Conway: “If Dürer never attained any clear grasp of the principles of perfect simplicity and perfect proportion, which were the secrets of the beauty of classical architecture, it was not for lack of willing and persistent study.” This sketch, as Conway notes, is part of a larger series of coherent, yet seemingly unconnected thoughts on architecture.

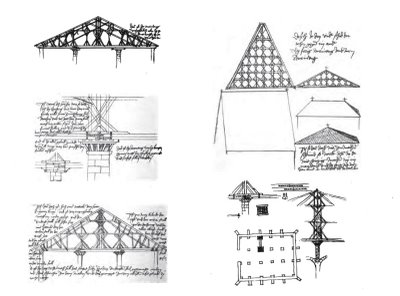

In 1525, Dürer was also commissioned to submit alternative schemes for a church roof in Nuremberg. Charged with replacing an old roof that was rotting away, Dürer’s notes and sketches show the artist replacing a high-peaked roof with a low-peaked solution – the result being a lightweight roof that could be supported by columns and minimal wood-bracing. These notes are significant for two reasons. On the one hand, they show Dürer working with an architectural plan. Along with his redesign for the roof, his plan shows an affinity towards a new spatial organization for the church with new spaces for kitchens and rooms. On the other hand, it is important to note that for this project, Dürer is asked to improve on an existing structure and issue a series of drawings detailing the modifications. Dürer would eventually realize these two impulses within the pages of the Etliche Underricht.

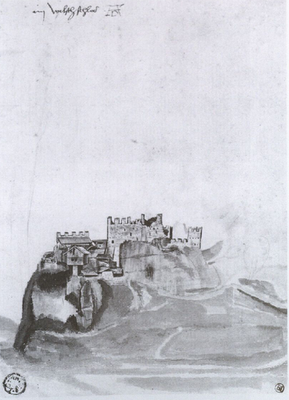

Dürer’s travels to Italy also provided the artist with architectural inspiration, as seen by a series of watercolors completed in the Autumn of 1494 and the Spring of 1495 (his Wanderjahre). Although some of these works -- such as these of a castle in Innsbruck -- tend to analyze the relationship between the vertical stonework and masonry and the flatness of the central square for a castle, others – like the watercolor of a castle in Val di Cembra – seem to analyze the location of a fortification in relation to its immediate landscape. Taken together, these watercolors provide a study of sorts: whereas one set considers a near-stereotomic approach, looking at the architecture of fortifications in terms of complicated layers of masonry and stonework, the other looks to the topography surrounding the subject.

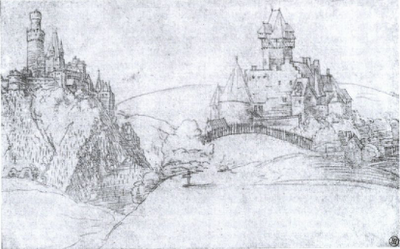

After his second trip to Italy, from 1512-13, Dürer began to write his Lehrbuch der Malerei (or Speis der Malenknaben), which contained two sections of note: one called "Von mos der pew" (“On the proportion of buildings”), the other "Daz fünft ein wenig vom gepew" (“The fifth capital: a bit on construction”). This text would eventually prefigure the more well-known Underweysung from 1525 and his Vier bücher von menschlicher Proportion, published posthumously in 1528. Dürer kept his interest in depicting architectural fortifications alive even during his trip to the Low Countries in 1520-21. In one of his sketches, Dürer places the Marksburg and Stolzenfels castles together on a singular mountainscape even though they are kilometers apart. It is a random placement – a capricious intervention that also signals Dürer’s own interest in a method for the site selection of fortifications along the German landscape. All these impulses – looking at a fortification in terms of sectional and topographic complexity, and placing fortifications in previously uninhabited areas – would become central to Dürer’s Etliche Underricht.

Before Dürer began working on his architecture treatise, Eastern Europe was engaged in a slow redoubt against advancing Turkish forces. In addition to Constantinople, which fell in 1453, Belgrade succumbed to Turkish armies in 1521. During that time, an anti-Turkish alliance of sorts was undertaken, arranged through the intermarriage of various crowns and bloodlines. This explains the appearance of a woodcut depicting a modified shield of Ferdinand I on the very first page of the Etliche Underricht. The shield contains heraldry from various areas. The two large lions represent Bohemia and Hungary. The smaller shield is split into four quadrants representing conflicts between Austria and Burgundy, Aragon and Sicily, Franche-Comte and Brabante. The small shield in the middle features a conflict between Tirol and Flanders. At the bottom, we see a pendant depicting the Order of the Golden Fleece, which surrounds the coat of arms. The appearance of this shield at the beginning suggests how we can look to the creation of the Etliche Underricht as an emergency architecture commission.

During the Diet of Nuremberg, from 1522-1523, the city inaugurated a committee of specialists to provide “the most educated solutions” for defending against a possible Turkish attack. Included in this committee were two Dürer’s closest friends: Wolfgang von Rogendorf, a military advisor to the crown, and the Moravian mathematician and military architect Johann Tscherte, a close friend of Willibald Pirckheimer’s. Dürer probably began learning about the urgency of countering the Turkish threat during his travels with Tscherte around Pavia from 1494-95. And on April 15, 1524, Tscherte wrote to Dürer, asking him to finish his “Instructions for measuring” as quickly as possible. This makes 1524 the year when Dürer most likely began working on the Etliche Underricht.

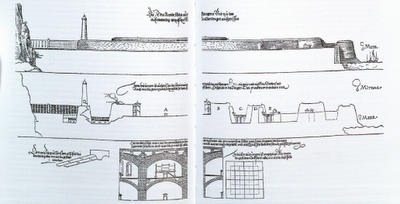

Dürer, Method for Planning a Fortification at Angled Town Wall, Woodcut from Etliche Underricht zu Befestigung der Stett, Schloß und Flecken (1527)

Dürer, Method for Planning a Fortification at Angled Town Wall, Woodcut from Etliche Underricht zu Befestigung der Stett, Schloß und Flecken (1527) Angled Fort with Graded Scarp, Plan, Section, Elevation, Woodcut from Dürer's Etliche Underricht (1527)

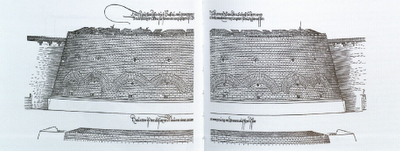

Angled Fort with Graded Scarp, Plan, Section, Elevation, Woodcut from Dürer's Etliche Underricht (1527) Fortified Citadel Situated between Sea and Mountains, Elevation, Section, Internal Section, Woodcuts from Etliche Underricht(1527)

Fortified Citadel Situated between Sea and Mountains, Elevation, Section, Internal Section, Woodcuts from Etliche Underricht(1527)

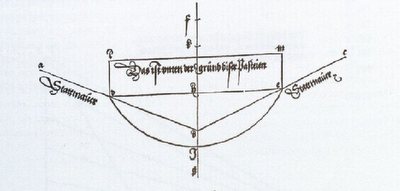

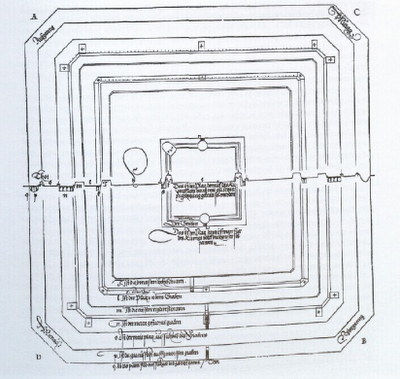

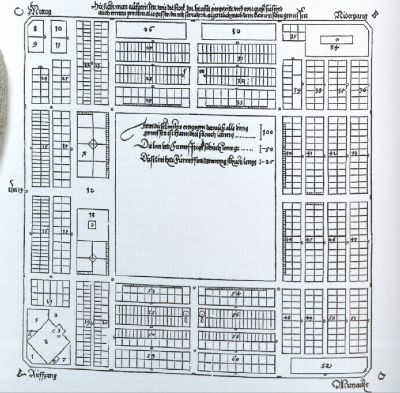

Woodcut of Ramparts Surrounding Fortfied Citadel, Plan, Inscribed Section (top), and Plan (bottom) (1527)

Woodcut of Ramparts Surrounding Fortfied Citadel, Plan, Inscribed Section (top), and Plan (bottom) (1527)A series of concentric, rectangular bastions – all designed according to Dürer’s specifications, surround the Royal garrison. For the Royal garrison itself, Dürer creates an orthogonal plan with a central square for the residence of a King. Around the residence, Dürer articulates a fairly normalized and rigorous spatial organization. Among a network of streets 50 feet wide, some 2,000 houses, stables, a Church, a Rathaus, magazines, armory, blacksmiths, and markets. The East corner of the City even features a Church. Houses behind the Rathaus are assigned according to kinship and rank, and other buildings are also arranged according to a prescribed division of labor: shopkeepers live near provisionary stores; armorers live near stables; clergymen live near the Church, et cetera. There are even separate bathhouses for men and women. All external bastions and walls are to be constructed from heavy stone, to protect from bombardment. The interior buildings are to be made of wood and stone, according to the size and importance of the structure.

To be sure, the Royal garrison from Dürer’s Entliche Underricht merits our attention for other reasons. Conway attributes a host of innovations to Dürer’s treatise: “The use of a polygonal form for the tracé of town fortifications; the use of well ventilated and lighted casemated batteries for the defence of trenches; the use of bomb-proof magazines and shelters; and the defensive interdependence of different parts of a fortress.” Others, like Hanno-Walter Kruft, locate the Etliche Underricht within a larger discourse about utopias and other ideal cities. Though Dürer’s treatise would be the obvious successor to works by Di Giorgio and others, it certainly should be considered alongside Serlio’s work as an exemplar of the relationship between ideal city forms and the complex spatial and hierarchical organizations within. And with regards to issues of site planning, Juan Luis González García observations about Dürer’s sketches of the Marksburg and Stolzenfels castles become important here – like the Royal garrison of the Etliche Underricht, these castles are depicted as if they were randomly placed on a landscape. This undergirds the ideal nature of Dürer’s fortified city – it is architecture that can be located practically anywhere.

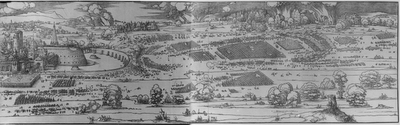

The only caveat -- as Dürer’s own drawings of the rounded block house show – is that in some circumstances, the particular nature of a site can place demands on the design of a fortification. Thus a block house situated between water and hills should take on a more rounded shape. For Dürer, then, the ideal city is a fortified city – the best case in point would be his 1527 woodcut Siege of a Fortress. Here, we see two cities. In the upper left, an agglomeration of unfortified buildings burn, while at the right, a fortified citadel featuring many of the innovations outlined by Dürer (rounded walls, protected casements, fortification of preexisting structures) appears relatively unscathed by the ensuing battle.

Yet in locating Dürer’s Etliche Underricht in a history of architecture treatises, some mention should be made about the degree of geometric formalism presented in the various woodcuts throughout the text. The drawings share an obvious affinity with many of the drawings from his Underweysung. Dürer’s very first lesson in the Etliche Underricht shows the adding of a circular rampart to a preexisting cornered city wall as a series of geometric iterations. Lines and arcs are measured and drawn according to a specific set of directions. Mario Carpo, in his Architecture in the Age of Printing, suggests that “Gothic architecture theory … privileged the control and the (often secretive) transmission of abstract geometric schemes.” Although there was nothing secret about Dürer’s geometries in the Entliche Underricht (a Latin translation appeared in 1535, and successive French and German editions appeared in 1603, 1823, 1840, and 1870), is it possible to claim that the treatise owes more to Gothic than to contemporary exemplars?

As is well known, Dürer had a personal, annotated copy of a 1505 edition of Euclid’s Elementorum (purchased during his second trip to Venice). But equally important is the fact that Dürer also had access to Willibald Pirckheimer’s personal library. There, Dürer would have encountered texts such as a 1498 edition of Polybius’ Historiae, a German translation of Flavius Vegetius' De Re Militari from 1474, as well as a 1521 edition of Niccolo Machiavelli’s Dell’arte della Guerra. But more importantly, the author had access to two vital texts: a 1512 edition of Alberti’s De re Aedificatoria, and a 1504 edition of Vitruvius’ Ten Books (this is not the illustrated version from 1512).

Kruft suggests that a likely inspiration for Dürer’s design of the Royal garrison is the 1524 Nuremberg map of Tenochtitlan, the seat of the Aztec empire. This was probably known to Dürer - a similar central square gridding also appears in Dürer’s treatise. But a closer glance at the text and woodcut images from the Etliche Underricht shows a decided Vitruvian influence. One case in point comes at the moment when Dürer describes the construction and siting of the Royal garrison. He writes: “The [fortified citadel] is to be built in the form of a square, each side of which shall have as much as 3400 feet of length. The site of the Castle is to be so chosen that the four strongest winds shall spend their forces against its angles.” Vitruvius, in the first book of his De Architectura, suggests an ideal, radial city plan that allows for orientation according to various winds. Yet in classical antiquity, the Vitruvian method was used to determine four cardinal points that were not only in relation to the wind, but that also facilitated the creation of orthogonal street grids. A look at the plan of Dürer’s Royal garrison not only shows the four cardinal points that create the building’s four corners, but also confirms how this set the stage for the creation of a gridded urban fabric within.

Dürer only makes a passing, cryptic reference to Vitruvius in the text of the Etliche Underricht. He writes of the Royal garrison: “The interior of the [fortified citadel] is to be thus arranged. In the midst is the Palace of the King, established on a site eight hundred feet square, and no corner is to be cut off from it. Vitruvius, the old Roman, plainly describes how such a royal palace should be built.” When we look at the center of the garrison, however, there is a blank space, a hole in the fabric. It is fitting that Dürer implores his reader to conjure a Vitruvian design for a royal residence – it is, in a sense, an ideal center for an ideal city.

This post has only begun to offer some possible directions for locating Dürer’s Etliche Underricht within a history of architecture treatises. Although its influence as a theoretical text remains to be analyzed, we know for certain that Dürer’s treatise inspired a so-called “German” type of fortification design. We also know that the Etliche Underricht inspired fortification designs in Nuremberg and Strasbourg. Despite the extent of the treatise’s influence, and despite the fact that few critical studies exist concerning this, as Dürer’s only text on architecture, the Etliche Underricht stands as a compelling, penultimate contribution to a vast body of work. Is it, as Pamela O. Long has described in her study of the Vitruvian Renaissance, evidence of Dürer’s “developed sense of his own originality and ownership”? At the very least, I have only begun to demonstrate how we can begin to understand the Entliche Underricht as a Vitruvian text.

________________________________________

Authors Note: Translations from German and Spanish are mine. Images come from the Spanish translation of Dürer's Etliche Underricht: Alberto Durero, Tratado de Arquitectura y Urbanismo Militar (Madrid: Ediciones Akal, 2004). Although there are countless texts on Dürer, Erwin Panofsky's The Life and Art of Albrech Dürer (Princeton University Press, 1943) and Giulia Bartum, Albrecht Dürer and His Legacy: The Graphic Work of a Renaissance Artist (Princeton, 2003) are standards. For more information related to this article, see (in no particular order) William Martin Conway, Literary Remains of Albrecht Dürer (London: Cambridge, 1889); Simon Pepper, “Artisans, Architects and Aristocrats: Professionalism and Renaissance Military Engineering” in David J.B. Trim, ed., The Chivalric Ethos and the Development of Military Professionalism (Boston, Massachusetts: Brill, 2003); Christopher Duffy, Siege Warfare (London: Routledge, 1979); Jãnis Langins, Conserving the Enlightenment: French Military Engineering from Vauban to the Revolution (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2004); Hanno-Walter Kruft, A History of Architectural Theory from Vitruvius to the Present, Ronald Taylor, Elsie Callander, and Antony Wood, trans. (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1994); Mario Carpo, Architecture in the Age of Printing: Orality, Writing and Typography in the History of Architectural Theory, Sarah Benson, trans. (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2001); Jukka Jokilehto, A History of Architectural Conservation (Oxford, United Kingdom: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2002); John Pinto, “Origins and Development of the Ichnographic City Plan,” The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 35, No. 1 (Mar., 1976), pp. 35-50; and Pamela O. Long, Openness, Secrecy, Authorship: Technical Arts and the Culture of Knowledge from Antiquity to the Renaissance (Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001).

3 comments:

fascinating stuff.

Do you suppose there a place for a contemporary architectural treatise on fortification design? In world war two it is a wind that carries bombers, and in the coldwar it is a nuclear and biochemical wind that orients the fortress. What, then, for today's fortress...

Ahh ... good question. I wonder if Nick Sowers will be responsible for the next "contemporary architectural treatise on fortification design"? Given the ascendancy of urban warfare, is it possible that any kind of tract about urbanism/urban design/architecture in the city becomes an unintentional treatise of fortification design? I wonder ....

you sure do deliver some scary thoughts mr. smokes.

Post a Comment

Links to this post

Create a Link